অনলাইনে সহজেই জমির নামজারি পদ্ধতি

মন্তাজ মিয়ার কাছ থেকে ৭ শতাংশ জমি কিনেছেন কামরুল ইসলাম। আর তাই অনলাইনে নামজারি আবেদন করতে ঢাকার ডেমরা থানার গৌড়নগর ৪ ইউনিয়ন ডিজিটাল সেন্টারে কয়েক দিন আগে এসেছিলেন তিনি।

কামরুল ইসলাম বলেন, “জমির নামজারি আবেদন অনলাইনে করার পদ্ধতি বেশ সহজ। আগে কাজটি জটিল ও সময়সাপেক্ষ ছিল।”

অনলাইনে সহজেই জমির নামজারি কীভাবে করবেন তা বিস্তারিত জানান ভুমি মন্ত্রণালয়ের স্বয়ংক্রিয় ভূমি ব্যবস্থাপনা সিস্টেম (অ্যালামস) মিউটেইশন কনসালটেন্ট মো. পারভেজ হোসেন।

তিনি বলেন, “জমি-সম্পর্কিত সাধারণ কিছু তথ্য জানা থাকলে বিষয়টি তত জটিল মনে হবে না।”

জমিতে মৌজা হিসাবে খতিয়ান নম্বর দেওয়া হয়। মৌজা হচ্ছে একটি জেলার অধীন ছোট আকারের এলাকা।

খতিয়ানের মধ্যে মালিকানার তথ্য (মালিকের নাম, জমির পরিমাণ ইত্যাদি) লেখা থাকে।

গত ১শ’ বছরে সরকার বিভিন্ন সময়ে জরিপের (সিএস, এসএ, আরএস, সিটি বা মহানগর, দিয়ারা ইত্যাদি) মাধ্যমে জমির মালিকানার রেকর্ড তৈরি করেছে।

একটি রেকর্ড থেকে হাতবদলের মাধ্যমে মালিকানার সর্বশেষ অবস্থা জানতে প্রতিটি পর্যায়ের খতিয়ান মিলিয়ে দেখতে হয়।

খতিয়ান পাওয়ার জন্য অনলাইনে আবেদন করলে আবেদনকারীর ঘরে বসে প্রিন্ট করে নিতে পারেন্।

ভূমি মন্ত্রণালয়ের ওয়েবসাইট থেকে জানা যায়- ২০২১ সালের ১ জুলাই থেকে সারা দেশে একযোগে শতভাগ ই-নামজারি বাস্তবায়ন কার্যক্রম শুরু হয়।

দেশের সব উপজেলা ভূমি ও সার্কেল অফিস এবং ইউনিয়ন ভূমি অফিসে ই-নামজারি চালু রয়েছে।

অনলাইনে আবেদনের সময় ১ হাজার ১৭০ টাকা অনলাইন পেমেন্ট করলেই ২৮ দিনের মধ্যে নামজারি সম্পন্ন করা যায়।

নামজারিতে নির্ভুল নাম লেখার জন্য জাতীয় পরিচয়পত্রের তথ্য-ভাণ্ডারের সঙ্গে আন্তসংযোগ করা হয়েছে।

চালু করা হয়েছে কল সেন্টার (১৬১২২)।

নামজারি আসলে কী

নামজারি বা মিউটেইশন হচ্ছে জমি সংক্রান্ত বিষয়ে মালিকানা পরিবর্তন করা।

কোনও ব্যক্তি বা প্রতিষ্ঠান কোনও বৈধ পন্থায় ভূমি/জমির মালিকানা অর্জন করলে সরকারি রেকর্ড সংশোধন করে তার নামে রেকর্ড আপটুডেট (হালনাগাদ) করাকেই ‘মিউটেইশন’ বলা হয়।

কোনো ব্যক্তির মিউটেইশন সম্পন্ন হলে তাকে একটি খতিয়ান দেওয়া হয় যেখানে তার অর্জিত জমির সংক্ষিপ্ত হিসাব বিবরণী উল্লেখ থাকে।

উক্ত হিসাব বিবরণী অর্থাৎ খতিয়ানে মালিক বা মালিকগণের নাম, মৌজা নাম ও নম্বর (জেএল নম্বর), জমির দাগ নম্বর, দাগে জমির পরিমাণ, মালিকের জমির প্রাপ্য অংশ ও জমির পরিমাণ ইত্যাদি তথ্য লিপিবদ্ধ থাকে।

নামজারি করলে নাগরিকের যেসব সুবিধা হয়

১. ভূমি সংক্রান্ত যে কোনো সেবা পাওয়ার জন্য সেবাগ্রহীতা অনলাইনে আবেদন করতে পারবেন।

২. অনলাইন পেমেন্ট গেটওয়ের মাধ্যমে ভূমি উন্নয়ন কর ও অন্যান্য ফি লেনদেন করা যাবে এবং এসএমএস/ইমেইলের মাধ্যমে প্রমাণকের নিশ্চয়তা জানতে পারবেন।

৩. জনগণ ভূমি নিবন্ধন, নামজারি, জমাভাগ ও জমা একত্রিকরণ (রেকর্ড সংশোধন), মৌজা ম্যাপ ইত্যাদি নকশা অনলাইন ওয়ান স্টপ সার্ভিস পদ্ধতিতে প্রাপ্ত হবেন।

৪. নামজারি-জমাভাগ ও জমা একত্রিকরণ (মিউটেইশন) প্রক্রিয়া সহজ ও সরল হবে; (ওয়ারিশ মোতাবেক হিস্যা নিশ্চিত হবে।

৫. ভূমির মালিকানা/স্বত্ত্বের ইতিবৃত্ত অনলাইনে পাওয়া যাবে।

৬. ভূমির দাগের ইতিবৃত্ত জানা যাবে।

৭. অধিগ্রহণকৃত জমির তথ্য, ক্ষতিপূরণ অনলাইন পেমেন্টের মাধ্যমে প্রাপ্তির নিশ্চয়তা থাকবে এবং তা সহজ ও সরল হবে।

৮. ‘রেন্ট সার্টিফিকেট’ মামলার অনলাইন উপাত্ত ভাণ্ডার হবে এবং সরকারের রাজস্ব আদায় বৃদ্ধি পাবে।

৯. খাসজমি বন্দোবস্ত প্রক্রিয়া সফটওয়্যার এর মাধ্যমে হবে।

১০. ‘সায়রাত মহাল ইজারা ব্যবস্থাপনা’ অনলাইনে হবে ফলে স্বচ্ছতা সুনিশ্চিত হবে।

১১. ভূমির মালিকানা স্বত্ব নিরাপদ হবে।

১২. দুর্ভোগ ও হয়রানি কমবে।

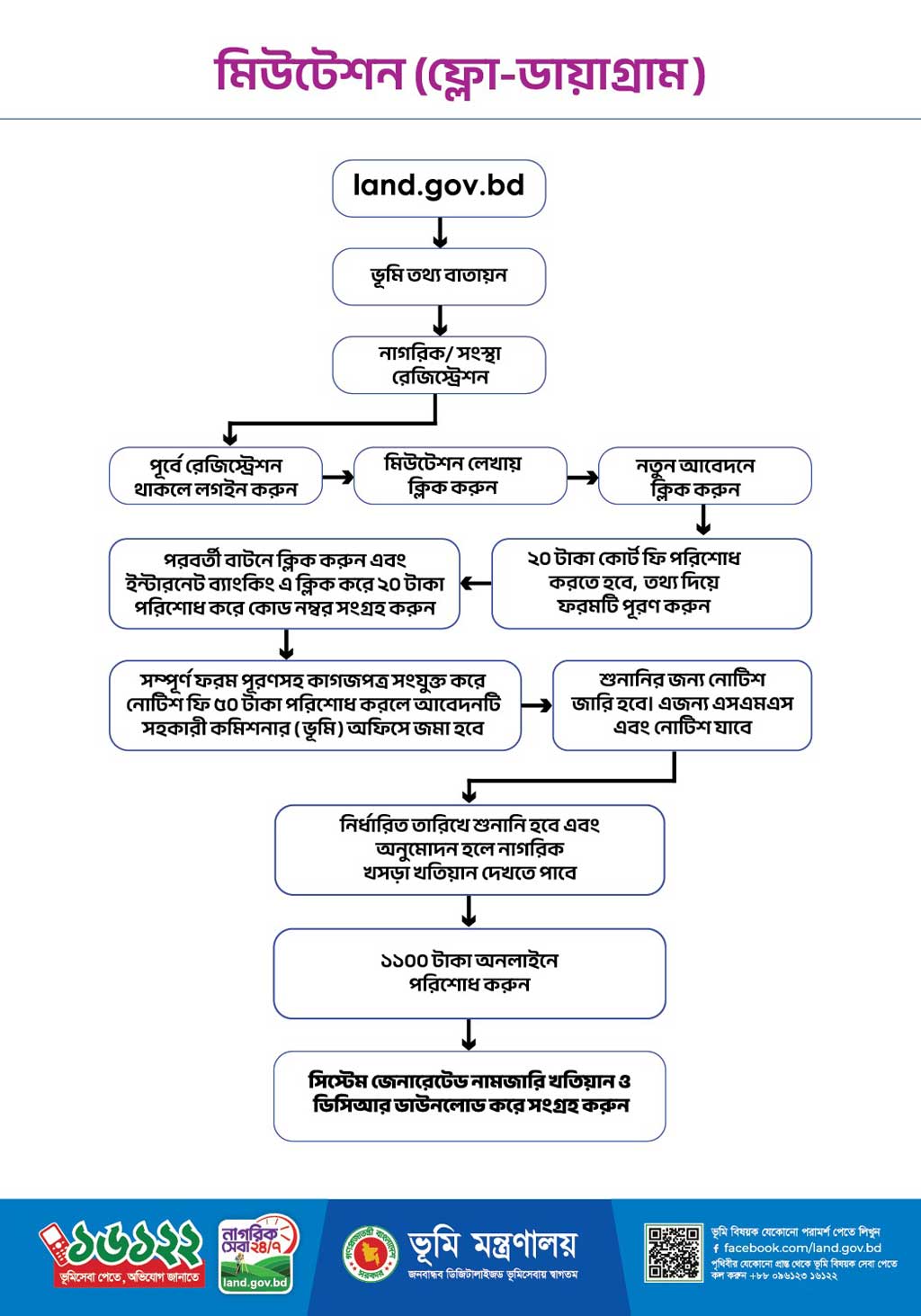

নামজারি যেভাবে করবেন

উত্তরাধিকার, ক্রয়সূত্রে বা অন্য কোনো উপায়ে জমির কোনো মালিক নতুন হলে তার নাম খতিয়ানভুক্ত করার প্রক্রিয়াকে নামজারি বলে।

উত্তরাধিকারসূত্রে মালিকানার ক্ষেত্রে আপস বণ্টননামা করে নিজ নামে জমির খতিয়ান করে রাখা প্রয়োজন।

ই-নামজারি করতে হলে

https://mutation.land.gov.bd/ ওয়েবসাইটে যেতে হবে।

এরপর ই-নামজারি আইকনে ক্লিক করে, মোবাইল নম্বর ব্যবহার করে নিবন্ধন করতে হবে।

নিবন্ধন হলে আইডি পাসওয়ার্ড দিয়ে জমির বা ফ্ল্যাটের প্রয়োজনীয় তথ্য পূরণ করতে হবে।

আবেদন ফি বাবদ ৭০ টাকা (কোর্ট ফি ২০ টাকা, নোটিশ জারি ফি ৫০ টাকা) অনলাইনে (একপে, উপায়, রকেট, বিকাশ, নগদ, ব্যাংকের কার্ড) পরিশোধ করতে হবে।

নামজারির হালনাগাদ তথ্য মোবাইল ফোন বার্তার মাধ্যমে জানা যাবে। অনলাইনে শুনানি করতে চাইলে ওয়েবসাইটে অনুরাধ জানাতে পারবেন।

আবেদন অনুমোদিত হলে নাগরিক ডিসিআর ফি ১ হাজার ১শ’ টাকা জমা দিলেই নির্দিষ্ট মোবাইল নম্বরে বার্তা আসবে।

এরপর নিজেই থেকে অনলাইন ডিসিআর এবং নামজারি খতিয়ান সংগ্রহ করতে পারবেন।

অনিয়ম হলে

ই-নামজারি বিষয়ে যে কোনো অনিয়ম হলে কল সেন্টারে (১৬১২২) ফোন করে এবং land.gov.bd ঠিকানার ওয়েবসাইটে অভিযোগ করা যাবে।

Source:

https://bangla.bdnews24.com/lifestyle/Jenerakun/632315991d16

Recent Posts

Recent Posts